© 2010 Christy K Robinson

This article is copyrighted. Copying, even to your genealogy pages, is prohibited by US and international law. You may "share" it with the URL link because it preserves the author's copyright notice and the source of the article.

All rights reserved. This book or blog article, or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the author except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

“It

is not the glorious battlements, the painted windows, the crouching

gargoyles that support a building, but the stones that lie unseen in or

upon the earth. It is often those who are despised and trampled on that

bear up the weight of a whole nation.” ~John Owen, English Puritan minister, 1616–1683.

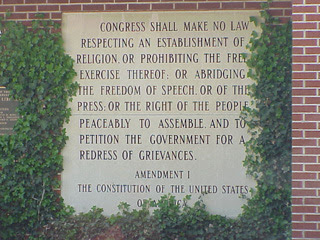

June

1, 1660 was a landmark date in American history. Its relation to civil

rights guaranteed by the US Constitution's Bill of Rights should be

noted, specifically the 1st Amendment regarding freedom of religion (to

worship or not, as your own conscience dictates), and freedom of speech

and assembly.

Mary

Barrett Dyer, hanged in Boston on June 1, 1660, was martyred for

liberty of conscience that Americans enjoy under the Constitution's Bill

of Rights. Other countries have modeled their constitutions and rights

on those of the United States, so these liberties have become global.

Torture and persecution

In

the late 1650s, Quakers had been persecuted for their nonconformism by

having their tongues bored with a hot awl; men and women were stripped

bare to the waist and flogged with up to 30 strokes of the

thrice-knotted lash, to add more injury to each stroke; they had their

ears either nailed to a post, or sliced off altogether; without a trial,

they were thrown in earthen-floored jail cells, sometimes for months,

with no candle or heat in New England’s harsh winters; prisoners were

beaten several times a week. Even non-Quakers whose consciences were

pricked by this harsh treatment were jailed, whipped, heavily fined, and

disfranchised (lost their civil rights and vote) for harboring or

sympathizing publicly with Quakers.

Contrary to popular opinion in genealogy sites, Mary Barrett Dyer wasn't hanged “for the crime of being a Quaker.” It wasn’t a crime to be a Quaker!

However, they didn’t attend Puritan worship or teaching services or pay

required tithes, didn’t keep the Sabbath holy, and criticized the

government leaders for their cruelty. Mary Dyer provoked her own trials

and execution for what we'd call civil disobedience, by repeatedly

defying the totalitarian Puritan regime headed by Massachusetts Governor

John Endecott. The Massachusetts Bay founders believed that religious

error or dissent from their dogma was treasonable.

Endecott,

a religious zealot, had a checkered past, leaving an illegitimate son

in England before he emigrated to Salem, Massachusetts in 1629;

treasonably cutting the “idolatrous” cross from the British flag; a

Massachusetts committee reported in 1634 “that they apprehend [Endecott]

had offended therein many ways, in rashness, uncharitableness,

indiscretion and exceeding the limits of his calling;” acting in ways

that endangered the patent that was their title to land in New England;

creating a mint in Boston that made unauthorized—and therefore

counterfeit—coins with a 1652 imprint for 30 years (so if the English

government confiscated the minting, Boston could claim the coins were

all from 1652 when they had little oversight during the English

political upheaval); and punishing his indentured servant girl with 32

lash-stripes and public humiliation for fornication, bearing a child out

of wedlock, and insistently naming his son as the predatory father

(which, of course, would make John Endecott the father of a rapist and

grandfather of a lowly servant’s bastard—can’t have that!).

The

colony and later state of Rhode Island was founded by Roger Williams

in the 1630s as a haven for freedom of conscience, and that’s where Mary

and her husband and children made their home after being ejected from

Massachusetts in 1637 over a religious matter prosecuted by the church

state. Mary studied Quaker beliefs in England for several years, and

returned to Boston only to be thrown into jail with no

notice to her husband in nearby Rhode Island.

Though

Mary could have lived out her life in safety, she believed she was

called by God to try the bloody religious laws of Connecticut and

Massachusetts, and she boldly entered their territory to both teach,

and support her Friends in the faith by visiting them in prison.

Prepared to die

Her

letters written from Boston prison to Governor Endecott, her actions,

and her statements at trial demonstrate to us that she willingly

sacrificed her life to stop the torture and persecution of people who

were obeying the voice of God in their hearts. She wrote, “Be not found

Fighters against God, but let my Counsel and Request be accepted with

you, To repeal all such Laws, that the Truth and Servants of the Lord,

may have free Passage among you and you be kept from shedding innocent

Blood…My life is not accepted, neither availeth me, in Comparison of the Lives and Liberty of the Truth and Servants of the Living God…

yet nevertheless, with wicked Hands have you put two of them to Death,

which makes me to feel, that the Mercies of the Wicked is Cruelty. I rather choose to die than to live,

as from you, as Guilty of their innocent Blood… Therefore I leave these

Lines with you, appealing to the faithful and true Witness of God,

which is One in all Consciences, before whom we must all appear; with

whom I shall eternally rest, in Everlasting Joy and Peace, whether you will hear or forebear: With him is my Reward, with whom to live is my Joy, and to die is my Gain.”

Knowing

that there was a death sentence hanging over her, she deliberately

avoided her husband who would have stopped her, and returned to Boston,

where she was arrested and jailed. She was convicted and condemned on

May 31, 1660, and was hanged the next day, on June 1.

The

shock over Mary Dyer’s death crossed the Atlantic immediately, and King

Charles II put an end to the New England death penalty for religious

practice, requiring that capital cases be tried in England. Public

outrage in New England over Mary’s death actually consolidated sympathy

for Quakers, Baptists, Jews, and others who refused to conform to

Puritanism. Even some of the New England Puritans demonstrated their

opposition to the harsh treatment of people of conscience, and suffered

imprisonment, banishment, confiscation of property, and heavy fines. A

number of those who’d suffered persecution converted to the Quaker

faith. Gradually, the torture and persecution slowed.

William

Dyer’s name appears on the 1663 royal charter granting rights of

freedom of religion to Rhode Island colony. He and several others had

worked closely with Dr. John Clarke of Newport, the architect of the

document, to preserve the separation of church and state, and promote

the freedom of conscience. One hundred thirty years later, the concept

became concrete in the US Constitution's Bill of Rights, Amendment I.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Reasonable, thoughtful comments are encouraged. Impolite comments will be moderated to the recycle bin. NO LINKS or EMAIL addresses: I can't edit them out of your comment, so your comment will not be published. This is for your protection, and to screen out spam and porn.