William and Mary Dyer

were citizens of Great Britain

who emigrated to New England in 1635 and co-founded the colony of Providence

Plantations and Rhode Island in 1638.

They were born during the reign of King Charles I, lived under Cromwell’s rule

in the 1640s and 1650s, and after Mary died in 1660, William lived during the

reign of Charles II.

Guest post © 2012 by Sarah

Butterfield, used by permission

Originally published on Sarah’s

History, 18 December 2012

“It’s only seven sleeps until Christmas Day!” was my dawn

chorus this morning. Tomorrow six, the next day five... My three children will

be practically exploding with excitement on Christmas Eve as they go to bed

full of anticipation for the wonderful day that lies ahead of them when they

wake up in the morning. Christmas Day is, for those that celebrate it, a day of

present exchanging, feasting and having fun. Imagine, then, if all of that was

taken away.

|

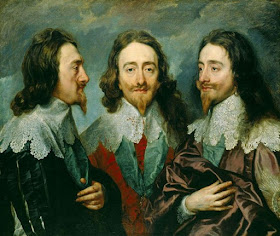

| Charles I triple portrait, painted by Anthony Van Dyke |

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms in seventeenth-century Britain were a

desperately unsettling time for the common people, as were the events that took

place before them. Charles I believed in his divine right to rule very

passionately, ruling without parliament for more than a decade. He also taxed

his people to breaking point; enforcing ship money in peacetime away from

coastal areas was one of his more unpopular moves. His poor rule over England and Scotland was one of the many

complex reasons civil war broke out between the crown and parliament in the

summer of 1642. At the same time, a form of Protestant Christianity known as

puritanism was on the rise. Puritans believed in the simplicity of faith. To

them, Christmas (among other celebrations) was an unnecessary Roman Catholic

tradition; they disapproved of celebrating the feast day, and the gluttony,

frivolity and excess that came with. In 1642, dedicated puritan soldiers and

members of parliament did not celebrate Christmas.

In 1643, the threat towards Christmas was more severe. The

parliamentarian leaders had signed a treaty with the Scottish in the autumn,

sealing themselves military support against the royalist army of Charles I. As

part of this treaty, parliament promised to further reform religion in England, bringing the faith of England closer to that of Scotland. The

Scottish had been practicing presbyterianism, another form of simple faith, as

their national religion for several decades. In the late sixteenth century

Christmas festivities had been stopped (save for a brief spell beginning in

1617 when James I reinstated them), and now England were expected to follow

suit.

|

| “Love

one another: A Tub Lecture Preached” by John Taylor, warned that Parliamentarian puritans were a threat to the celebration of Christmas in January 1643. |

The English puritans followed the Scottish Presbyterian

lead, treating Christmas Day in 1643 as a day like any other. Shops were opened

and church doors closed. Puritan members of parliament went to work at the

Houses of Parliament, leading where they expected subjects to follow. John

Taylor’s satirical pamphlet ‘Tub Lecture,’ published earlier that year, had

become a gloomy reality. Still, the civil war could have gone either way, and

Christmas wasn’t legally banned—yet.

In 1644, the non-celebration of Christmas became more

extreme again, as the feast day clashed with a puritan fast day. Members of

parliament favoured the fast over the feast; remembering their own sins as well

as the sins of their ancestors for indulging themselves during the twelve days

of Christmas. Parliamentary power was ever increasing by this time, and

Charles’ power slipping away.

|

Oliver Cromwell,

successful soldier, parliamentarian and Puritan |

Christmas 1645 was equally, if not more solemn than that of

the year before. In 1645, Oliver Cromwell and Thomas Fairfax had created their

New Model Army. Their army was structured, disciplined and puritan in the

extreme. In addition to these qualities the army was incredibly powerful, and

all but destroyed Charles’ royalist forces during two crucial battles—Naseby and Langport—that summer. Charles was captured and

handed over to the Parliamentarian army. Decisions were to be made about

Charles’ status now, but one thing was sure in the minds of parliament; they

had won the war. Charles would be their puppet ruler. Earlier in 1645,

parliament had issued their alternative to the Book of Common Prayer, ‘The New

Directory for the Worship of God’; the book did not mention Christmas at all.

With the king defeated, Christmas was gone. It was noted that man could walk

the streets on Christmas Day in 1645, and have no idea that it was a Holy feast

day.

|

| John

Taylor published another pamphlet in 1652, titled “The Vindication of Christmas,” supporting the continuing celebration of Christmas. |

Still, England’s

Anglican subjects did not want to give up Christmas without a fight. John

Taylor published another pro-Christmas pamphlet, ‘Complaint of Christmas’,

persuading his fellow Christian men to continue celebrating Christmas in

defiance of parliament. This the people did, and more besides. On Christmas Day

1646 men celebrated as normal, and attacked local tradesmen who had opened

their shops for business as if it were a normal day.

June 1647 saw an act pass through parliament. Christmas was

now a banned celebration, and anyone caught celebrating could be lawfully

punished. This act was highly unpopular throughout the country, and sparked the

pro-Christmas riots that erupted all over the country on Christmas Day that

year. Holly was hung in blatant defiance of the new law. Shops that were open

for business were attacked and smashed to pieces and men were killed.

Shortly after Christmas Day in 1647, Charles I opened

communication with the Scottish to free himself from captivity and rule in his

own way again. This sparked a second English civil war between parliament and

crown; this time, however, the conflict was short-lived and parliament enjoyed

a decisive victory the following August. Christmas 1648 passed with Charles

imprisoned and parliament in charge. In January 1649, Charles was tried, found

guilty and executed for high treason against his country. The war was over, and

Christmas was gone. The parliamentary ban of Christmas held fast, with Oliver

Cromwell continuing the law after he was named Lord Protector of England in

1653. Of course, just because Christmas was banned didn’t mean people didn’t

celebrate it. They just did so in secrecy.

|

| Charles II: The king who brought back Christmas! |

In September 1658, Oliver Cromwell died and was replaced as

Lord Protector by his son, Richard. (Interesting move for a man who was against

the hereditary monarchy, but that’s a moan for another day.) Richard was an

unsuccessful Lord Protector, and the people of England decided they wanted a

monarch after all. Charles II was recalled from exile and restored to the

throne in 1660. He brought with him the restoration of Christmas, which was a

hugely popular and successful move. Hurrah for Charles II! No wonder he was

such a popular king.

__________________

Further Reading-

“The Rise and Fall of Merry England: The Ritual Year 1400-1700″ by Ronald Hutton, Oxford University Press, 1994.

“Cromwell: Our Chief of Men” by Antonia Fraser, Phoenix Books, 2008.

“The English Civil Wars” by Blair Worden, Phoenix Books, 2009.

PS: I know it wasn’t technically all Cromwell’s fault, I

just thought that title sounded pretty cool.

_____________

Sarah Butterfield is a

history student living in Derbyshire, England. Visit her blog, Sarah’s History, for

her studies in English history.