This article is copyrighted. Copying, even to your genealogy pages, is prohibited by US and international law. You may "share" it with the URL link because it preserves the author's copyright notice and the source of the article.

I have been researching and writing a nonfiction biography about Anne

Marbury Hutchinson. Someone who negatively

reviewed one of my Dyer books complained that some of the articles were taken

from this Dyer blog, which costs me thousands of hours in research and writing

time, and money spent on research books--but is provided at no cost to readers. With that sort of critical attitude, I decided to remove or heavily edit

some of the articles from this blog, to make my books even more exclusive than they had been. "The Great Frost" is one of those articles.

In this era when publishing companies and print periodicals

have gone out of business, it's silly to dismiss websites and blogs as being

wildly speculative or unsupported opinion. I know scores of historical authors

and researchers who will agree with me that blogs are legitimate sources of

research, infotainment, and newly discovered fact, as well as corrections to

fanciful antiquarians of the 18th and 19th centuries.

When I researched the Dyer books, I read literally hundreds

of books and scholarly papers about their culture, beliefs, and practices,

spoke with experts and scholars, and I visited the places I was writing about.

In the Hutchinson book, there's a very long bibliography at the end.

This article, excerpts of a chapter of the Hutchinson book, is about an event that

took place when Anne Marbury (not yet Hutchinson) was a teenager living with

her family in London. Her father was a popular minister and had authority over

several churches at the time.

The Great Frost

excerpts from the book,

Anne Marbury Hutchinson: American Founding Mother

excerpts from the book,

Anne Marbury Hutchinson: American Founding Mother

© 2017 by Christy K

Robinson

T

|

he

Great Frost of 1608 began in December 1607, when a massive freeze descended on

Great Britain, Iceland, and Europe. It enveloped city and country alike,

freezing animals and people, stopping trading ships, sending icebergs on the

North Sea between England and the Continent, and freezing seaports so that

coastal shipping trade came to a stop for three months.

“The first decade of the 17th century was marked

by a rapid cooling of the Northern Hemisphere, with some indications for global

coverage. A burst of volcanism and the occurrence of El Niño seem to have

contributed to the severity of the events. … Additional paleoclimatic, global

evidence testifies for an equatorward shift of global wind patterns as the

world experienced an interval of rapid, intense, and widespread cooling.”

Schimmelrnann,

Lange, Zhao, and Harvey, abstract,

The Peruvian silica volcano, Huaynaputina,

erupted in 1600, with so much ejecta that more than 12 cubic miles of rock and

ash filled the atmosphere, causing rapid global cooling and catastrophic

weather events for a decade, including a Russian famine that killed two million

people, epic mud flows in California, great droughts and freezes that affected

the Popham and Jamestown colonies in Virginia, and die-offs in European vineyards.

The far-off Peruvian volcano affected Great Britain, too.

Perhaps to profit from the phenomenon of a

once-in-a-lifetime cold spell, an anonymous author wrote a 28-page book, The Great Frost: Cold doings in London,

except it be at the Lottery, With

newes out of the country. A familiar talke betwene a country-man and a citizen

touching this terrible frost and the great lotterie, and the effects of them.

the description of the Thames frozen over, which may have a longer title

than the interior text. The cover says it was printed on London Bridge (then

supporting shops and tenements above the shops), so undoubtedly the book was

meant to be sold on the frozen river below. There were two characters, the Countryman

and the Citizen, having a dialogue about the first Frost Fair ever held, and

the economic conditions of England because of the extended freeze.

In the city, the Frost Fair meant that shops

could set up market tents on the frozen river that “shows like grey marble

roughly hewn” and sell souvenirs and

winter clothing and shoes, serve alcohol from bars on wheels, gamble on sports

or animal baiting, provide hot fair food from fires built on the ice (I wonder

if they deep fried odd things as we do now), and have sleigh rides up and down

the river. Ice skating was well-known in the Netherlands and Germany, and

perhaps the English tried it. They also played football, and shot arrows and

muskets. The Citizen said: “Both men, women, and children walked over, and up

and downe in such companies, that I verily believe, and I dare almost sweare

it, that one half (if not three parts) of the people in the Citie, have been

seene going on the Thames.”

And right there in London, probably out on the ice

on a Saturday, we’d find the Marbury family, listening to musicians and

watching dancers, playing, and eating fair food like turkey leg, meat or fruit

pies, and gingerbread.

With little or no firewood or coal, people shared

beds, mixing up aunties and grandchildren, parents and babies, servants and any

guest staying the night. They had cupboard beds or four-posters with a canopy

and curtains to keep their body heat and warm breath captive. The large Marbury

family would have shared beds and body heat at night.

With commercial traffic stopped in its tracks

during the Great Frost, the merchants, warehouses, dock hands, ship crews, and

others were forced into stoppages they called “The dead vacation,” “The frozen vacation,” and “The cold vacation.” We can imagine the

effect on their economy, especially if they were living hand to mouth.

Coupled with the loss of work and

little to sell in the shops, the price of food rose

precipitously. “For you of the

country being not able to travel to the City with victuals, the price of

victail [victuals, food] must of necessity be enhanced; and victail itself brought into a

scarcity,” wrote the Citizen.

The church poor rolls, the parish charity for widows and orphans, would

have been stretched past their limits when they experienced weather and

epidemiological catastrophes, so of course the Marburys would have been no

stranger to hard work, short rations, and sharing small spaces.

The Great Frost was harsh, and it wasn’t the only time the Thames froze,

but it was the most memorable. It

lasted a little more than three months until the ice broke up and life

returned to normal. Well, normal for them. Warmer meant…

|

| Table from page 49 of

Schimmelrnann,

Lange, Zhao, and Harvey, abstract,

http://aquaticcommons.org/14822/1/Arndt%20Schimmelmann.pdf that gives extreme climate events in the early 1600s. Click image to enlarge. |

*************

Christy K Robinson is author of these books (click the titles):

We Shall Be Changed (2010)

Mary Dyer Illuminated Vol. 1 (2013)

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This Vol. 2 (2014)

And of these sites:

Discovering Love (inspiration and service)

Rooting for Ancestors (history and genealogy)

William and Mary Barrett Dyer (17th century culture and history of England and New England)

|

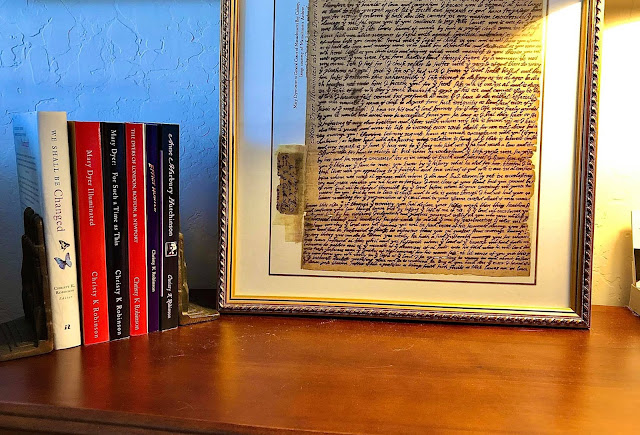

| Books by Christy K Robinson, with a framed print of Mary Barrett Dyer's handwritten letter to the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony, October 1659. |