© 2022 Christy K Robinson

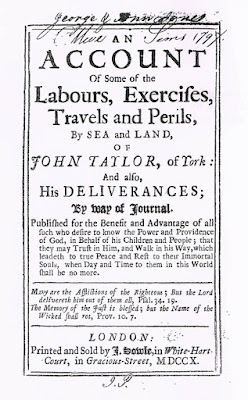

In the winter or early spring of 1657, Mary Dyer had returned from a four-year stay in England. Based on the timeline of a ship's voyage, she probably left Bristol around the end of December or early January. The ship fought heavy storms in the North Atlantic (which is why winter voyages were uncommon), and the captain was forced to sail past Boston all the way to a winter haven in Barbados. We know the ship stayed in Barbados for a few weeks because of two documents: a letter from Henry Fell to Margaret Fell, and the journal of John Taylor, which described Mary in glowing terms.

The ship left Barbados for Boston at about the middle of March, probably making a stop or two as it sailed north. When it arrived in Boston Harbor, the captain was ordered to show any Quakers known to be on board. The colony had created laws between August and October of 1656, ordering the whipping and jailing of Quakers, and the burning of their books and papers. Mary and her companion Anne Burden would have been aware of the laws when they landed in Barbados and stayed with Quakers there.

The women had decided to sail to Boston anyway, though they could have found ships bound for New Amsterdam (New York) or Rhode Island. When they arrived in Boston, probably in late March, they were arrested on the ship and dumped in the prison in Boston, there to languish for months. They were committed to "close confinement" so that "none could come at them."

How do we know? The Massachusetts General Court met in mid-May, and Mary was not on the docket, though she should have been. Her husband William was Solicitor General of Rhode Island, and he was engaged in Rhode Island colonial business during their May court sessions and elections, unaware of Mary's arrest and incarceration during that time. Anne Burden was not allowed to take care of her late husband's business affairs in Boston, but was banished and sent back to England after about three months in prison, during which time she was very ill.

These events give us an approximate timeline of Mary Dyer's first time in prison. After her husband William learned of her harsh treatment, he made an appearance in Boston and had her released. They would have ridden horses on the Post Road back to Rhode Island, a distance of perhaps 60 miles through farmlands and forest wilderness, crossing rivers and creeks. The journey needed to be as quick as possible, because Mary had been banished by Gov. John Endecott’s court, and that distance would probably mean at least two days of horse riding.

In my book, Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (Vol. 2 of The Dyers), I used those deductions to dramatize Mary's and William's reunion after several years apart.

The images here are sidesaddles of the type ridden by women in the early and mid-17th century. Women didn't often ride astride because of their undergarments (or lack of them), their skirts hitched up over their ankles which was immodest, and they didn't wear breeches unless they were "that" kind of woman. So they rode by sitting sideways on the back of a horse, with their skirts modestly draped around them, turning forward to guide the horse. Women riders rested their feet on the platform (planchette). Yes, there was a risk of sliding off.

One of the things an author needs to research is how people moved about in their world. I had to learn about how women rode horses in the 1650s. It required core strength to sit sideways and turn forward to guide the horse, and after a two-month stormy voyage followed by solitary confinement for three months, Mary would not have much strength or muscle tone. I decided (as the author, 356 years later) that she must have ridden some or most of the distance astride on her horse, or astride on William's.

After 1830, women hooked one knee over a second, lower pommel and put the other foot in the stirrup, as in this blue and red saddle.

********************

Christy K Robinson is author of these books (click the colored title):

And of these sites:

Discovering Love (inspiration and service)

Rooting for Ancestors (history and genealogy)

William and Mary Barrett Dyer (17th century culture and history of England and New England)